Hof der dingen - Commemorative tiles

Between 1850 and 1930, an estimated 150,000 Belgians emigrated to North America. They fled a country plagued by famine, failed potato and grain harvests, epidemics, the collapse of the flax industry, and high unemployment rates.

Roughly half of these emigrants were destitute farmers from rural West and East Flanders. The United States and Canada welcomed them with open arms — both countries desperate for labourers. Many ended up in Ontario, Canada’s agricultural province, where they first joined the work force harvesting sugar beets and later ended up in tobacco cultivation.

Tens of thousands of others settled in the U.S. state of Michigan, most of them finding employment in Detroit’s booming auto industry. The Flemish newcomers naturally gravitated toward one another, forming close-knit communities with their own pubs and leisure clubs, even hosting Bruegel-themed festivals and Belgian-style fairs.

It’s in this context that, on August 13 of 1914, a new newspaper was born: the Detroit Gazette, created specifically for Flemish immigrants in the United States and Canada. Its founder and editor-in-chief was Camille Cools, who had moved from Moorslede to Detroit with his family in 1889, when he was just 15 years old.

Before long, the Gazette had a network of around twenty correspondents across Flanders, the U.S., and Canada. Cools’ mission was clear: to help Flemish immigrants maintain their connection with their homeland, the Dutch language, and their own culture and traditions.

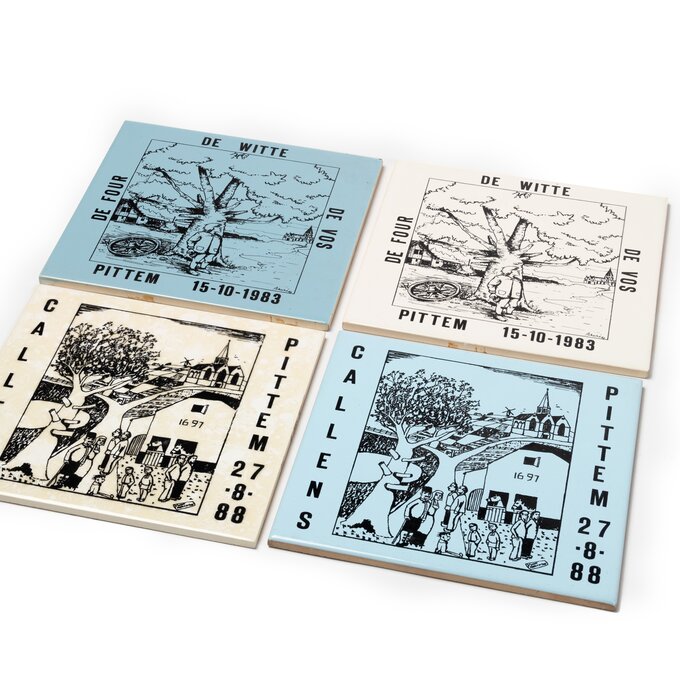

And that connection with the Flemish home front never fully faded. Even today, descendants often cross the ocean to reconnect during family gatherings. At these reunions, commemorative tiles are exchanged, such as the two shared with us by Paul Callens.

He recounts: “We gave these two tiles to participants at our family gatherings in the 1980s. The people who crossed the ocean held on to them — we later found them among their collection of special keepsakes. They kept coming, and we kept going. The bond between West Flemish people can’t simply be cut. Their dialect may be fading, but their connection remains.”